Grief or Rumination? When anxiety hijacks the grieving process

Many of us have experienced what feels like an endless loop of thinking —trying to figure out why something happened, what it means, and what we should do next. This looping, churning thought process can feel urgent and important. But more often than not, these energy depleting attempts to figure out what the bad thing is (or is not) and how to make it better isn’t insight or problem-solving at all. It’s rumination, and it’s born out of anxiety, not grief.

Understanding the difference between the sadness of grief and the rumination that results from anxiety and depression is essential for emotional processing and, ultimately, healing. Often conflated, these two emotions serve very different purposes in our nervous systems.

This article covers the following:

What is grief, actually?

What is rumination, and why does it feel productive when it isn’t?

What does the threat-response cycle have to do with rumination?

How does co-regulation make grief tolerable and transformative?

Why does grief sometimes turn into anxiety?

How can people who struggle to access sadness begin to grieve?

How can the experience of rumination be used to access grief?

What even is grief?

Grief is a holistic biological process that is activated whenever we face an unwanted reality we cannot change. This may include

a loss of what was (people, roles, health, stability)

a loss of what should have been (our hopes or imagined futures)

a loss of control, influence, or certainty

disruptions to identity or relationships

losses of safety, predictability, or meaning

missed opportunities or the passage of time

the collapse of ideas, institutions, and beliefs (true or untrue) that serve as a foundation to our sense of safety or security

Bereavement is a category of grief. It is loss through the death of a loved one.

Each of these experiences confront us with the limits of our own power — our inability to reverse a fact or outcome we do not want. Grief is the process that allows our bodies to “digest” that unwanted reality. Typically, there is a non-linear pattern to grief that includes:

Denial is a psychological defense related to cognitive dissonance: we don’t want the new reality. And sometimes, that new reality is so big and scary that our brains cannot synthesize the new reality with the way things were and are expected to be.

Bargaining is an attempt to negotiate a past, current, or future reality - we are trying to reduce or eliminate the impact of the thing we do not want. Sometimes, in order to hold the illusion of power and control, it feels better to feel guilty about what we did not or could not do than it does to integrate the new reality which includes our powerlessness.

Humans really do hate to feel out of control. We want to know what is going to happen and to have control over the outcome - so much so that sometimes we feel deeply ashamed for what has happened even when we know intellectually that it’s not our “fault”. This experience is embodied powerlessness - often it feels like shame. And when we assign meaning based on our body sensation (emotional reasoning) we can sometimes develop a narrative that implicates us in the thing we are grieving. And that can complicate our grief process.

Anger protects from the vulnerability of sadness and the boundary violation of the thing we do not want. Anger shows up in two basic scenarios for humans: we’ve suffered a boundary violation or we feel threatened. Grief can be both - the thing we do not want to happen ruptures the boundary of any of the needs on the hierarchy. Additionally, the thing we do not want to be real can be profoundly threatening.

Anger is our mammalian response to threat. It is sympathetic nervous system activation: fight/flight/freeze/appease. We can be deeply and actively angry at abstract ideas or events - and our mammalian bodies can hold a fight or flee response for some time without a clear threat to fight or flee from. Sympathetic activation without a clear object to fight or flee from results in generalized embodied anxiety. We have an incomplete threat cycle when we do not move from anger to sadness.

Sadness actually heals - but it’s most efficient with co-regulation. Sadness heals the wound of powerlessness most effectively in connection with at least one safe, attuned other. Sadness is a dorsal vagal experience. Socially, sadness is mediated by ventral vagal stimulation - social engagement: holding, rocking, hugging, touch, face to face contact, nurturing, care, active listening, acceptance of the full range of feelings.

When humans are grieving, it can feel like a deep, scary well - we can feel trapped, alone, afraid, and inexplicably ashamed. When we are grieving in the calm, accepting presence of an attuned and caring other, that dorsal process is mediated by warmth, connection, acceptance. Shame and anxiety grow in alienated or secret or simply under-supported grief - when we don’t (or can’t) reach out for support.

Connection and care support a grief process even when anger and sadness are present so that anxiety and shame are much less present. Sadness is the most powerful emotion in grief because it is the feeling that transmutes a threat response - our activation response to a thing we do not want - to one of relatively calm resignation to a reality we cannot change. Without sadness, we remain activated: fearful, angry, disoriented, intolerant of the new reality - which can pull us out of connection with other important relationships and roles.

Acceptance is a misnomer. It’s more like a resignation to the new reality. We can tolerate it. Acceptance doesn’t mean we live warmly with the new reality. We may actually hate it forever. But this phase of grief is about holding the new previously scary and threatening reality with more regulated resolve. We are no longer fearful or rageful of the new reality and have come to tolerate it with less sympathetic nervous system activation.

Supported sadness is the path to this regulated state. We are not numb. We are not avoidant. We are not distressed. We hold the new reality with care and resolution. We can feel a sense of hope again. We can imagine a life worth living beyond the new reality. And sometimes we can think about the loss with love and gratitude rather than fear, anger, sadness, or despair.

Meaning making is an important part of the grief cycle. Typically we make meaning of the bad thing we did not want after we’ve come to a place of calm resignation. In this part of the pattern, we may educate others, work on prevention, commit to acts of service or acts of connection, memorialize a person or an idea. We make meaning with our lives related to the new reality we did not want when we were first confronted with it. We are in a stable place of emotional regulation. We are not fearful or rageful or avoidant or intolerant. The new reality just is. And we are committed to working within its implications.

Grief is not a linear process. We can move in and out of the phases of grief. In a healthy grief process, the waves come high, frequently, and long at the beginning of the new reality. But when we spend time with the thing we do not want, when we look at it, feel our anger, feel our sadness, receive support in the way that our bodies feel safest (food, care, comfort, parallel activities, proximity, physical contact, warm presence)*, our bodies can move through the sadness toward acceptance. We feel less anger, less fear about what the new reality means about us, others, the world, our future. Presence allows us to be sad and face the bad thing.

For many adults, sadness was not met with warmth or attunement in childhood. Without early co-regulation, sadness becomes coded in the nervous system as unsafe, overwhelming, or shameful—so the body avoids it. Anxiety is more familiar - so our threat response stays to help . . . But if we are not accustomed to experiencing sadness with social support, a strange thing can happen. . . Without a supported or grounded grief process, our minds often shift into threat orientation. We try to identify, clarify, prevent, or solve the threatening, bad thing. Our minds turn the problem over and over, desperately trying to regain control.

*This is a description of ways that we can “process grief”. See “How to Maintain or Return to Grief Instead of Spiraling (further) Into Anxiety” toward the end of this blog for a brief description of what “processing grief” is not. Either can be a helpful definition.

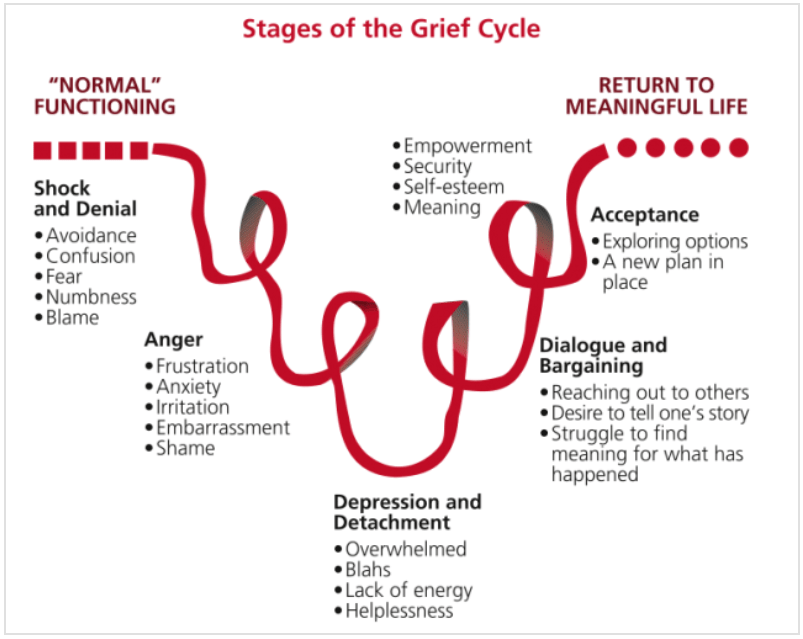

A non-linear grief cycle

Rumination: Anxiety’s Attempt to Find Certainty

Rumination happens when the mind tries to define, clarify, prevent, or solve a threat that is not clearly identifiable or solvable.

You’ll know you’re ruminating when your thoughts keep circling around:

Something bad happened but I’m not sure what it was exactly, and I need to know

Something bad happened, and I believe I could have done something to stop it or mitigate it (but I did not know it was going to happen or that it was happening or that it could happen or I did not actually have the ability to prevent or stop the bad thing from happening).

something bad that might happen, but I don’t know when

something bad that might happen, but I don’t know how or what it is

something bad will happen but I’m not sure how to predict or stop or solve it

something bad will happen, but I cannot actually stop it

The felt sense of rumination is increasing anxiety over time. The more you think about what the problem is or how to solve it, the more activated and distressed you feel. Rumination, a cognitive process that happens in our cerebral cortex, entices the sympathetic nervous system with the illusion that if we think hard enough, we will gain control or certainty. The sympathetic nervous system wants to orient to the threat and take action (fight, flight, or at the very least appease/fawn). But the key problem is this:

It is not possible to take physical action to deal with a threat that is vague, hypothetical, or unsolvable.

Our big human brain is trying hard to work with our mammalian body, but our bodies do not have a clear threat to fight, flee from, or fawn over. This leaves your body stuck in an activated threat state without a pathway to complete the cycle or return to calm. Our bodies can take action if the threat is definable and can be fought or fled from. Things that we cannot fight or flee from that will not kill us immediately are left for grief to work through. Grief brings clarity. Grief opens up our options in ways we cannot imagine when we are ruminating, preventing grief from doing its important work.

Why We Ruminate: A Nervous System Perspective

When mammals perceive novelty in the environment, we orient ourselves to the novelty. That is, we look in its direction, listen for it, feel for it - we try to determine what it is so that we can respond to it effectively. If the novelty feels threatening, our bodies focus in on it more intensely. That is, our brains use all of our senses and life experience to define the threat so that we can either fight or flee (or fawn/appease) If the threat is a rustling in the dark, we reflexively peer into the darkness to try to make out the threat. Our pupils dilate to narrow the range of vision and increase visual sharpness. “Time slows” because our limbic systems (our amygdalae and hippocampi) are capturing minute details of the experience. We move more quickly but with less precision. These physiological changes are due to the Threat Response Cycle, described by Peter Levine, PhD (Somatic Experiencing).

THE THREAT RESPONSE CYCLE

The threat response cycle is a hierarchy of responses that are triggered, initially, by novelty in the environment. For ease of discussion, each of the phases of the sequence is presented separately. In actual threat response, the movement from perception of threat into active defense may happen in milliseconds, with no apparent transitional phases. Likewise, in an over-responsive nervous system, startle may be the habituated response to any novelty in the environment, but it won’t be followed by specific defense when there is no actual threat.

The cycle progresses as follows:

1a Arrest response/preparatory orienting — When there is novelty, we stop and notice the external environment. We evaluate whether or not the stimulus is threatening.

1b Startle — The startle may happen almost simultaneously with the arrest response. The difference between the two is that the startle has a higher level of sympathetic arousal and actively begins the preparation for action. It includes mobilization of the chemical and physical resources needed to respond to the threat.

2 Defensive orienting response (DOR) — The potential for threat is assessed as being high; orienting is now done in the context of specific threat and the need for more detailed assessment of that threat. Activation level is usually moderate to high.

3 Specific defense

● Fight: we move toward the threat and engage to stay safe (like fighting a fire)

● Flight: we move away from the threat and disengage to stay safe (like running from a burning house)

● Freeze: we cannot determine whether fight or flee improves our chance of survival or we assess that becoming imperceptible increases our chances of survival

● (Appease/Fawn) - delay the fight/flee until it’s safe to do so

4 Completion — If threat doesn’t actually threaten, our bodies return to the resting state after activation level is reduced via normal self-regulatory processes. If a threat requires fighting or fleeing, the fight, flight or freeze sequence that allows us to survive the threat allows us to move through and use the high (sympathetic) activation levels of the threat response, and our bodies return to equilibrium via normal recovery processes. Yay! We survived!

5 Exploratory orienting response (EOR) — Relaxed alertness to both internal and external environment; curiosity; gathering information about the environment with a low level of activation.

Sometimes. . . . Rumination hijacks Step 2 (the Defensive Orienting Response).

The body and mind try to orient to a threat that may not clearly defined (or is undefinable). This is most often the case when a threat is an idea rather than a physical reality.

The mind cannot make sense of what the threat actually is. This can happen when our brains cannot comprehend what we are seeing or experiencing.

The mind cannot make sense of how to fight with or flee from (or fawn/appease toward) the threat. It cannot determine: fight, flee, freeze, appease.

So the body cannot complete the cycle. Our brains spin like a Macbook wheel—processing but not completing.

Macintosh spinning wheel of stuckness

Our brains want to figure out the threat and find a plan to reduce the distress. When grief is processed like a threat, we get stuck. We suffer from chronic anxiety and the illusion that continued thinking is necessary for safety - because we have to figure out a plan for this problem. But anxiety is for survival. Grief is for processing realities we do not want - even if the new reality feels threatening.

Grief transforms us most efficiently in connection and co-regulation with another safe other

Grief processes facts in the present and past, things that have already happened that you are reckoning with:

something happened,

you couldn’t stop it,

you didn’t want it,

and you are powerless to change it now.

Grief is the process that allows your body to “digest” powerlessness and come back into homeostasis—into what often feels like calm resignation.

In early childhood or from about the time we start to walk or move around independently, we start to reckon with things we want but cannot have and/or cannot control. When we start to gain independence to get what we want, we then have to reckon with things we cannot have. During this period of time, we need competent protectors to both keep us safe from the things that we want but will hurt us or others AND provide comfort for us as we grieve for the things we want but cannot have. Typically developing children in secure environments protest: they cry, yell, stomp, hit, hold their breath, throw things, bang on things, and, well, throw full on tantrums when they do not get the thing they want but cannot have. Tantrums, it seems, are abbreviated grief processes: denial (protest: “no!”), bargaining (“but I want it!” - later, negotiation), rage (screaming, yelling, hitting, stomping), sadness (remorse, seeking comfort, crying). . . acceptance. Our general advice for parents is to provide presence, attunement, warmth, and comfort for their child while they grieve the thing they cannot have. The parents’ calm, regulated attunement and warm acceptance of their child’s grief provides co-regulation for the child’s nervous system. Co-regulation supports the grief process and allows the child to move through it with fewer complications. . .

So what do our childhood tantrums (or lack thereof) have to do with our grieving process?

We adults develop the ability to grieve effectively with the help of emotionally attuned caregivers who can tolerate our sadness, anger, and longing. But if we didn’t have enough of this kind of co-regulation, grief may feel unfamiliar, foreign, threatening, and unbearable as adults. We are uncertain about what it’s for, when it will end, and what to do with it. Without the embodied experience of supportive co-regulation, grief can feel cold, dark, isolated, lonely, and endless. In short, grief can feel intolerable.

When we cannot tolerate grief, we turn away from the present or past loss and instead generalize our sense of powerlessness into the future.

That’s when grief becomes unadulterated fear of what might happen or what this might mean about ourselves, others, the world, our future experiences - instead of sadness about what has already happened.

And fear is the fuel of rumination. Our fear hijacks our grief process. Generally, the more lonely and isolated we are from supportive others who might provide co-regulation, the more anxious we are.

Generalizing Powerlessness Into the Future (Cognitive distortions are a feature, not a bug):

Over-generalization is a common thinking error—one of many “cognitive distortions” built into our mammalian threat system. In a milieu where our threats are more specific to life and death, these “cognitive distortions” keep us alive:

A rustle in the grass might be a predator. And whether it is a predator or not, our generalization and emotional reasoning (that is, assessments or judgements that come from an emotion or body sensation) keep us alive whereas ignoring our feelings and body sensations may have resulted in the termination of our life and, subsequently, our genetic line. Fear is the survival emotion.

A familiar pattern in a natural ecological milieu with seasonal patterns of nature often does correlate with resources or danger. It’s a good idea to have a tornado shelter during tornado season. And it’s a good idea to know the seasonal signs of tornado season if there happens to be a tornado season where you live. Our brains detect patterns and are particularly adept at generating conclusions based on what we know and feel. . . in the natural world. This super power is less useful in a less predictable, less cyclical world with more abstraction and far less certainty.

But in a world largely disconnected from seasons, patterns, and evolutionary relationships, where there is more nuance, the threats are less clear, the actions are less discernable, and there is generally less certainty, these biologically useful thinking patterns can lead us astray. If we are interacting with the experience of grief, of powerlessness, as a threat, our threat response system will reasonably generalize powerlessness to similar future experiences, and it makes us afraid that we will either never have again the thing we are grieving or we become afraid of the very thing we feel lost without (i.e. love, connection, security).

When we generalize powerlessness into the future, our narrative minds tell stories like:

“I’ll never love again.”

“My child will never be okay.”

“I’ll never feel safe again.”

“We’ll never regain stability.”

“Our friendship will never recover.”

“I will never feel safe again.”

“I’ve failed. I’m unhireable.”

“The [religious institution] is corrupt, and I’ll never know what I really believe.”

“I will never stop feeling gutted about my loved one’s death.”

These are all normal, if fleeting, thoughts in the denial and bargaining phases of grief. They can feel really scary. Our brains are trying to process this new, terrible reality. But when we are unable to find our way to sadness, anxiety stays to help us with the threat. We avoid the powerlessness with the illusion of control - often because we are unaccustomed to working through grief with support. Because we are anxious, and our nervous systems prefer certainty over uncertainty, we try to solve the problem our anxiety is creating.

We ruminate to figure out what to do about this scary set of predictions rather than allowing the sadness to bring us to a sense of clarity and calm resignation about the new reality.

We try to solve the problem rather than allowing ourselves to be sad. The rumination feels urgent—even though it is a trap that increases anxiety and decreases clarity. Trying to solve the problem without the clarity resulting from the grief process keeps us anxious. We cannot think or see clearly. And all of the unsuccessful attempts to clarify or solve the problem make us feel increasingly powerless. Anxious rumination adds the illusion of ongoing powerlessness to an already tender state resulting from true powerlessness. The real bummer of all of this is that anxiety prevents the power of supported sadness from doing its life sustaining work. The grief process is disrupted by anxiety - so often we mistake achingly long periods of anxious rumination for processing grief. And many of us thing, “what’s so great about sadness, anyway? It feels awful!” Anxious rumination and grief are very, very different experiences.

How to Maintain or Return to Grief Instead of Spiraling (further) Into Anxiety

Many of us, unfortunately, have not had successful grief experiences. That is, we have not had the experience of grief bringing us from the shock or denial of the first moments of learning about the immensely threatening thing we do not want to a relatively gentle state of resignation. It’s a powerful process. For many of us, when we are asked to “process our grief”, we have no idea what that means. For many years, this was my own experience. What does processing grief even mean? For we who are more comfortable with narratives and cerebral experiences, there is an effective invitation into grief. More relevantly, we can use the more familiar, sometimes compelling process of rumination to access the unfamiliar process of grief. . .

Incidentally, spending time with the thing we do not want, looking at the thing we do not want, feeling our anger, feeling our sadness, receiving and accepting support from others - this is what is meant by “processing”. The opposite of processing is avoiding places, people, objects, or activities that remind us of the loss; avoiding thoughts, feelings, or memories associated with the loss; emotional numbing (of sadness, anger, and despair but inevitably ALL emotions since we cannot selectively numb); using substances, goals, activities, or roles to avoid feeling the sadness, anger, or despair.

This strategy was developed for the folks who have difficulty accessing and naming their emotional experiences, folks who have not had enough of the co-regulation needed to be able to process powerlessness in a way that does not feel life-threatening - folks like me. Below is a grief-processing structure that helps you name some of the things that you wanted and what is the new (seemingly intolerable) reality: what happened, what you hoped for, and what you feel—without slipping into future-based fear.

A Simple Structure for Processing Grief

Start by acknowledging sadness or anger:

I am sad/angry that:

…(describe one facet or consequence of the event, fact, or loss you cannot change)

2. Then explore your expectations and reality:

I thought or wished that:

…(what you wanted to happen).But what really happened is:

…(the actual outcome).

3. Continue naming what is true:

I am sad/angry that:

(list as many truths, facts, feelings, and observations as needed).

4. Then reconnect to hope:

I hope/wish that:

(a hope is what you desire moving forward, a wish allows your desire regardless of what is actually possible).

5. Finally, notice:

feelings (emotions: happy, sad, mad, afraid, disgusted, embarrassed, guilty, ashamed, etc.)

body sensations (tense, full, loose, lightening bolts, butterflies, stiff, sore, open, spacious, warm, tingling, buzzing, shimmering, stabbing, throbbing, twitchy, etc.)

urges (I need to. . . ; I am doing … automatically)

thoughts

meaning-making patterns

One way to spot meaning-making is to complete the chain:

“If ___ happened, then that means ___, which means ___, which means…”

This brings awareness to the spiraling cognitive distortions that fuel fear and despair:

Replacing Rumination with Grief

When you are grieving and catch yourself thinking about the future, ask yourself, “am I sad or angry about what has happened? Or am I worried or fearful about what this means about the future?” Bring your attention to the anger or sadness about what has already happened and what it means to you - what has been lost? Use the simple structure for processing grief as a cognitive exercise. If you are able to tolerate company - an attuned, warm, present person - you will have to wrestle less with isolation, shame, and anxiety. The co-regulation is a grounding force in our nervous system that allows the dorsal vagal work of grief to stay balanced in the social engagement system of the ventral vagal system. Socially supported grief is a productive process - it brings us back to meaning, to purpose, to life when we are facing soul-crushing loss.

This process (above) can take 2-5 minutes or a couple of hours - whatever your body wants and can tolerate. Some of us cannot access sadness. . . yet. This process is meant to create a cognitive framework to start with and allow feelings to show up - to your level of tolerance. Even a few minutes of honest, grounded cognitive grieving allows you to process your real, actual, life altering loss rather than experiencing the scary generalizations our threat response system makes about what the loss means.

Rumination = trying to identify or solve a possible future threat

Grief = allowing the body to settle into sadness around a clear past or present loss

One increases anxiety.

One reduces it.

The more comfortable you (and your supportive others) become with supported grief—the sadness, the anger, the disappointment— the better you’ll actually feel. We try to avoid sadness because it’s scary. But redirecting your thoughts to what is known to be true rather than fearing the future is a game changer. Your body will know the difference.

Feelings wheel by artofit.org